As to whether we should simply “trust the Founding Fathers,” it must be noted that they were not all of the same mind on the subject of representation. They argued about it more than any other subject at the convention.

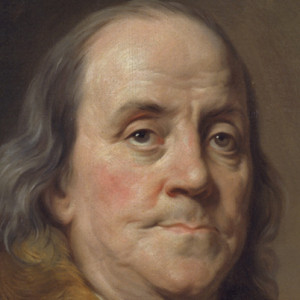

Benjamin Franklin advocated representation in proportion to quotas of contribution or population with remarkable consistency over several decades.

- June 8, 1754: In preparation for the meetings that would produce the Albany Plan, Franklin proposed: “One member to be chosen by the Assembly of each of the smaller Colonies and two or more by each of the larger, in proportion to the Sums they pay Yearly into the General Treasury.” The Albany Plan ultimately proposed from 2 to 7 representatives per colony, while retaining proportionality with quotas of contribution. It was not ratified.

- July 21, 1775: Franklin drafted an “Articles of Confederation” for a “United Colonies of North America.” It included the following: “The Number of Delegates to be elected and sent to the Congress by each Colony, shall be regulated from time to time by the Number of such Polls return’d; so as that one Delegate be allowed for every [5000] Polls. And the Delegates are to bring with them to every Congress, an authenticated Return of the number of Polls in the respective Provinces which is to be annually triennially taken for the Purposes above mentioned.”

- July 30, 1776: In the post-Declaration debates over the Articles of Confederation, Franklin was prescient. “Let the smaller Colonies give equal money and men, and then have an equal vote. But if they have an equal vote without bearing equal burthens, a confederation upon such iniquitous principles will never last long.”

- August 1, 1776: He continued in fine rhetorical form a few days later. He “thought it a very extraordinary language to be held by any state, that they would not confederate with us unless we would let them dispose of our money. Certainly if we vote equally we ought to pay equally: but the smaller states will hardly purchase the privilege at this price.” Despite the power of these arguments, the Articles of Confederation provided for equal state representation without also providing for equal state contributions.

- August 20, 1776: As the president of the convention to draft Pennsylvania’s constitution, Franklin authored (but did not submit) a document to protest the draft of the Articles of Confederation. “And therefore the XVIIth Article, which gives one Vote to the smallest State, and no more to the largest when the Difference between them may be as 10 to 1, or greater, is unjust, and injurious to the larger States, since all of them are by other Articles obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective Abilities.”

- September 28, 1776: The new constitution of the state of Pennsylvania established proportional representation while rebuking the existing draft on the Articles. “But as representation in proportion to the number of taxable inhabitants is the only principle which can at all times secure liberty, and make the voice of a majority of the people the law of the land…”

- June 11, 1787: At the Constitutional Convention, Franklin clearly stated his preference. “I now think the number of representatives should bear some proportion to the number of the represented, and that the decisions should be by the majority of members, not by the majority of the states”

- June 11, 1787: Franklin proceeded to make the first of several proposals to reconcile his principles with the demands of small-state delegates. “Let the weakest State say what proportion of money or force it is able and willing to furnish for the general purposes of the Union. Let all the others oblige themselves to furnish each an equal proportion…The Congress in this case to be composed of an equal number of Delegates from each State…If these joint and equal supplies should on particular occasions not be sufficient, Let Congress make requisitions on the richer and more powerful States for farther aids, to be voluntarily afforded, leaving to each State the right of considering the necessity and utility of the aid desired, and of giving more or less as it should be found proper.”

- June 30, 1787: “Let the senate be elected by the states equally–in all acts of sovereignty and authority, let the votes be equally taken — the same in the appointment of all officers, and salaries; but in passing of laws, each state shall have a right of suffrage in proportion to the sums they respectively contribute.”

- July 3, 1787: With the small states refusing to back down, Franklin made the proposal that was the basis for the resolution of the conflict. “That all bills for raising or apportioning money, and for fixing salaries of the officers of government of the United States, shall originate in the first branch of the legislature, and shall not be altered or amended by the second branch; and that no money shall be drawn from the public treasury, but in pursuance of appropriations to be originated in the first branch. That in the second branch of the legislature, each state shall have an equal vote.”

- July 6, 1787: Franklin half-disavowed his proposal and suggested getting rid of the Senate. He “…did not mean to go into a justification of the Report; but as it had been asked what would be the use of restraining the 2d. branch from medling with money bills, he could not but remark that it was always of importance that the people should know who had disposed of their money, & how it had been disposed of. It was a maxim that those who feel, can best judge. This end would, he thought, be best attained, if money affairs were to be confined to the immediate representatives of the people. This was his inducement to concur in the report. As to the danger or difficulty that might arise from a negative in the 2d. where the people wd. not be proportionally represented, it might easily be got over by declaring that there should be no such Negative: or if that will not do, by declaring that there shall be no such branch at all.” Franklin was a funny guy. His July 3 proposal passed anyway on July 16.

- September 17, 1787: Franklin declared his intent to sign the proposed constitution and to not criticize it, and asked the same from the other delegates. “Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good — I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad — Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die — If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavor to gain partizans in support of them, we might prevent its being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects & great advantages resulting naturally in our favor among foreign Nations as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent unanimity. Much of the strength & efficiency of any Government in procuring and securing happiness to the people, depends. on opinion, on the general opinion of the goodness of the Government, as well as well as of the wisdom and integrity of its Governors. I hope therefore that for our own sakes as a part of the people, and for the sake of posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution (if approved by Congress & confirmed by the Conventions) wherever our influence may extend, and turn our future thoughts & endeavors to the means of having it well administered.”

To my knowledge, he kept his word about not criticizing the representational design of the Senate after the Convention, as did, mostly, the other Founding Fathers who opposed it. But he knew the representational design of the Senate was wrong. He went along with it after sustained intransigence from the small-state delegates led him to believe that the alternative was no constitution at all.

I welcome other relevant primary sources on Franklin and representation. I haven’t read them all.

Franklin deserves special esteem for his struggle against slavery. It is fair to say that he believed in the proposition that all men are created equal more than any other delegate at the Convention.

For less serious Franklin wit and wisdom, see here and here.