Why do we still have the Electoral College? This is a root-cause analysis.

Republicans are opposed to reform. That’s part of the answer. (Thought experiment: would Democrats support the EC if it advantaged them?) Another part (maybe): battleground states like the attention. Another: small states have a disproportionately large number of EC votes.

But the main reason is simply that the Constitution is so hard to amend. The hardest in the world, actually. (Do Americans even know this?) There are two methods of proposal and ratification, but to keep it simple: 2/3 of the House, 2/3 of the Senate, ¾ of state legislatures.

Why is the Constitution so hard to amend? (This is what root-cause analysis is. Keep asking why.) Or, where did these fractions come from? You won’t find the answer in The Federalist or in the letters or speeches of the FFs.

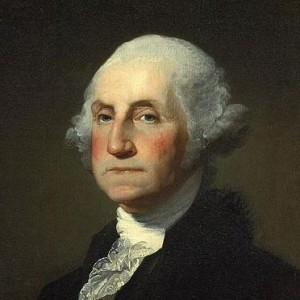

The answer is in Madison’s notes at the Convention on September 10, 1787. That’s when the basic structure of Article V was set. By that time, the primary decisions about the Constitution had been made.

September 10: Gerry (MA) described the design they had tentatively agreed to as he understood it: 2/3 of states can call a convention, and a majority can ratify. He expressed doubt about the last part.

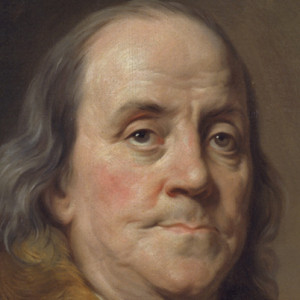

Hamilton (NY) supported majority ratification and suggested 2/3 of the House and Senate could alternatively propose amendments.

Sherman (CT) proposed unanimous state ratification.

Wilson (PA) proposed ratification by 2/3 of state legislatures. His motion failed 5 states to 6. (For: NH, PA, DE, MD, VA; Against: MA, CT, NJ, NC, SC, GA.) He then proposed ¾, which was accepted without a vote.

John Rutledge (SC) proposed that two provisions be unamendable: one protecting the slave trade until 1808, and one mandating that direct taxes be proportionate to the census (which would prevent Congress from imposing a direct tax on slavery). The Convention agreed.

September 15: Sherman made a number of proposals to make Article V more difficult. Most were rejected (supported by CT and NJ only), but they wound up adding, “”that no State, without its consent shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.”

The next why: Why did 6 states vote against ratification by 2/3? Rutledge’s slavery-related unamendable provisions are the clue for 3 of them. The other clue was the angry debate over the slave trade in August.

The Deep South delegates voted against 2/3, read the room and agreed to ¾, and proposed the unamendables.

In August, the Northern states and Upper South states expressed strong opposition to the slave trade. Rutledge: “If the Convention thinks that N. C. S. C. & Georgia will ever agree to the plan, unless their right to import slaves be untouched, the expectation is vain.”

CT and NJ surely voted against 2/3 to protect equal state suffrage in the Senate. MA voted against 2/3 probably because they were rattled by Shays’ Rebellion.

Why did Hamilton and Wilson propose 2/3s for proposal and ratification? It is less clear, but they knew full well who wanted what to be difficult to amend. They had decided long ago to favor union above all. We should not construe 2/3 as what they thought best.

So, why do we still have the EC? Because, while a majority of Americans support its removal, the Constitution requires an even larger supermajority for amendment, AND…

…the Constitution is so difficult to amend because it was, among other things, a complicated answer to a riddle: how do thirteen mostly independent states in the New World reconcile a minority whose priority is the preservation and expansion of slavery…

…with a majority whose priorities are a common defense against European powers, economic stability, and republican government?

The answer: republican government with pro-slavery provisions (fugitive slave clause, three-fifths, slave trade until 1808, limits on powers of Congress, limits on taxation), and an extremely difficult amendment process.