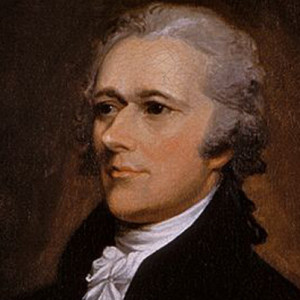

Prior to the Convention, Hamilton’s writings about government focused on the need for the central government to have greater powers, to the exclusion of any concerns about representational design. At the Convention and during the ratification process, Hamilton was a strong and consistent advocate for proportional representation.

- May 30, 1787: Immediately after the introduction of the Virginia Plan at the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton moved that “the rights of suffrage in the national legislature ought to be proportioned to the number of free inhabitants.”

- June 18, 1787: Hamilton attacked equal state suffrage in the New Jersey Plan and proposed proportional representation. “Another destructive ingredient in the plan, is that equality of suffrage which is so much desired by the small States. It is not in human nature that Va. & the large States should consent to it, or if they did that they shd. long abide by it. It shocks too much the ideas of Justice, and every human feeling. Bad principles in a Govt. tho slow are sure in their operation and will gradually destroy it….The Senate to consist of persons elected to serve during good behaviour; their election to be made by electors chosen for that purpose by the people: in order to this the States to be divided into election districts.”

- June 29, 1787: “The question, after all is, is it our interest in modifying this general government to sacrifice individual rights to the preservation of the rights of an artificial being, called States? There can be no truer principle than this-that every individual of the community at large has an equal right to the protection of government.”

- November 21, 1787: In the Federalist No. 9, Hamilton wrote, “A distinction, more subtle than accurate, has been raised between a CONFEDERACY and a CONSOLIDATION of the States. The essential characteristic of the first is said to be, the restriction of its authority to the members in their collective capacities, without reaching to the individuals of whom they are composed. It is contended that the national council ought to have no concern with any object of internal administration. An exact equality of suffrage between the members has also been insisted upon as a leading feature of a confederate government. These positions are, in the main, arbitrary; they are supported neither by principle nor precedent…..”

- December 14, 1787: Hamilton continued in the Federalist No. 22, “The right of equal suffrage among the States is another exceptionable part of the Confederation. Every idea of proportion and every rule of fair representation conspire to condemn a principle, which gives to Rhode Island an equal weight in the scale of power with Massachusetts, or Connecticut, or New York; and to Deleware an equal voice in the national deliberations with Pennsylvania, or Virginia, or North Carolina. Its operation contradicts the fundamental maxim of republican government, which requires that the sense of the majority should prevail. Sophistry may reply, that sovereigns are equal, and that a majority of the votes of the States will be a majority of confederated America. But this kind of logical legerdemain will never counteract the plain suggestions of justice and common-sense.” Hamilton made no attempt to reconcile his views with the representational design of the Senate. Criticism of the Articles is the text; criticism of the proposed Senate is the subtext.

- June 20, 1788: At the New York Convention, Hamilton explained why the compromise was necessary, but does not defend it as just. The “…small states, seeing themselves embraced by the Confederation upon equal terms, wished to retain the advantages which they already possessed. The large states, on the contrary, thought it improper that Rhode Island and Delaware should enjoy an equal suffrage with themselves. From these sources a delicate and difficult contest arose. It became necessary, therefore to compromise, or the Convention must have dissolved without effecting any thing. Would it have been wise and prudent in that body, in this critical situation, to have deserted their country? No. Every man who hears me, every wise man in the United States, would have condemned them.”

The other two New York delegates to the Convention, Yates and Lansing, left the Convention early on. According to the rules at the Convention, each state delegation had to have two members, so Hamilton became a delegate without a vote. Yates and Lansing left because they felt they did not have the authority to participate in drafting a new Constitution and because they opposed greater powers for a central government. They opposed proportional representation as well. They are not on the $10.

Like Franklin, Hamilton also opposed slavery through much of his political career.